One step forward, one step back?

Saisiyat and Han commingling during the Pasta‘ai ritual in Taiwan

Mark van Tongeren, independent scholar, Taiwan

Providence has it that the music I’m going to talk about the Pasta’ai Ritual is only happening every two years. And, that today, it is about to start. I am prepared to leave very soon for the ceremony, the ritual, which will last three full nights. I have first been attending this ritual at 2004, 16 years ago. And now, after 16 years, I feel ready to try to start saying something about this intricate, very fascinating ritual. So I feel kind of blessed by the spirits of the KuKu Ta’ai, who this ritual is devoted to. That I have been so busy preparing both this talk, which I am so excited to share with you, as well as doing this at the time of the ritual. The time slot for the ritual is really one month, and we are supposed to sing the songs of the ritual only in this one month. I feel so fortunate that I could be so busy with this talk at the time the Saisiyat is busy preparing themselves, and I join their singing rehearsal several times.

I am talking about the Saisiyat people. The Saisiyat people live in the north-west of Taiwan, on the slice you see there. And they are minorities among the minorities, of course, all the minorities together is just a tiny population of the population of Taiwan. And, these minorities, the Saisiyat people, only numbered around 6,600 people, which is not much of course. They live in different communities, which are scattered since Japanese time, when they separated this two community.

The Ta’ai are a drawf people, a dark people that once live here, but they were wiped by the Saisiyat, so the story goes. And, what I am going to talk about is the questions of non-Saisiyat people joining the ceremony as a possible threat to the preservation of this tradition, of Saisiyat knowledge, and also of the spacial-tempo organization of the pulses of the music and the dance together.

To start with the first question, there are lots of people coming to the ceremony now, I read a figure of up to 20,000. The question is, do these people disturb the ritual or not. To get some insight into this question. I really have not been able to find out a lot by myself, because my Chinese only is getting more and more to a point where I can talk more and more to the local people. They don’t speak Saisiyat. Actually, they do speak Chinese mostly. But I rely on this thesis by Jia-Yu Hu, which gives me a lot of insight into the identity of the Saisiyat.

So, it turns out the Saisiyat has been inter-mingling with other tribe around them, already for many centuries. And that they are quite open to do so. It’s effected them to the custom, which they adopted; language, names, which they adopted, most people use Chinese names now; technologies, imported from other tribe, other people, or colonizer. Also inter-marriage and adoption, these have happened in the past, and still happens nowadays.

So the openness of the Saisiyat is so strong, the acculturation is so strong that many people ask themselves: how can it be that they still have their own identity, that is so strong? They have always have these ambiguous relationships with other people, looking up to the superiority of people, who are numerically larger than themselves, even when they are in larger number in the past; technologically more advanced, maybe magical power, like the Ta’ai they wiped out. These are the people that brought them benefits, they needed, that they wanted that. But it was also a disadvantage.

The story of the Ta’ai, that is of course, the crucial thing here. It goes like this. Ta’ai were the people who lived very close to the Saisiyat, as another tribe. They interacted often. They learned from them, how to improve their agriculture, they looked up to their magical skills. But the ta’ai were also going after their woman. One time, after a feast, the Ta’ai went back again to their own territory. A man of the Saisiyat discovered that a Ta’ai man had slept with his woman, and he went after them. There was a place where they used to rest, on a tree, a large branch sticking out over an abyss with the river below. He was so angry that he made them all tumble down the river, and they died. There were only man who survived, and they came back to the tribe, and they said: “what you have to do now is to learn our dances and song, and to keep them alive, this is your duty, otherwise, some really bad thing is going to happen to you.” This is still something very much felt, very much believed still by the Saisiyat nowadays, even though it happened hundred of years ago.

This was so difficult even they though they have dance and sung together at many occation, it turned out to be so difficult. So these two man, found that only one family was able to do these dances and singing, and this family still leads the singing and the dancing.

There is a common pattern, not only about ta’ai, maybe the saisiyat are jealous about, maybe technology or other things of other people that their action causes loss, death, and even extinction. There is regret about that, and there is suffering from the consequences.

From Hu Jia Yu’s Thesis, I paraphrase the following part:

A paradoxical emotional complex is emphasised in the oral transfer of myths and shapes the characteristic ethos of the Saisiyat people. The relations with the Other apply to mythological beings such as the ta’ai, who very much exist still as spirits. But they may also be extended to real world neighbours such as the Atayal, the Han Chinese and the Japanese who ruled Taiwan from 1895 to 1945.

I wanted to quote another part, she said:

“Through cyclical ritual performances, ties between the present time and the ancestors’ time are significantly established; new elements adjusted to the contemporary world are also forged wherever possible.

In this aspect, a vision of the collective Saisiyat past presented in ritual operations has achieved a remarkable degree of internal integration across geographic, linguistic, and cultural barriers.”

(Chia-Yu Hu. Embodied Memories and Enacted Ritual Materials. Possessing the Past in Making and Remaking Saisiyat Identity in Taiwan, 2006: 128)

so this explains, how the Saisiyat can maintain a very strong identity despite adopting so many things from colonizer and tribe around them.

What I take from whose thesis is that:

Pasta'ai was never exclusively for or about the Saisiyat alone. It was always about the Other. The Saisiyat self-consciously (re)negotiate relations with powerful others. They assimilate to a large extent, but retain a remarkable sense of their identity through the performance of many rituals.

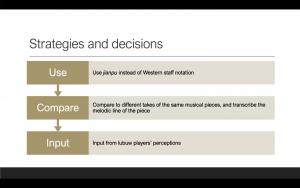

The question is now, what allows this commingling to happen? For that I’m going to look at the spatio-temporal organisation of overlapping pulses of music and dance in the Pasta’ai.

I will focus on the last Pasta’ai I joined, except for the one I’m going to join hopefully tonight. In the northern group of the Saisiyat. I will focus on the main three nights, the whole ritual last about a month.

I will argue that the Pasta’ai in Wufeng has a consistent performance of four parts with different tempi. So not a polyrhythmic structure but different tempi. And I will coin this a multitempic structure. I will argue that this requires considerable skills of those who sing and dance, despite the superficial simplicity of many movement (dance) and sound (music) parts. Thirdly, I will argue that this seeming simplicity of most movement (dance) and sound (music) parts allows for the ritual to open up to participation of complete outsiders. Because it seem simple, it’s inviting for others to join.

These four parts, they are divided across the bottom bell, flags, songs, and the line dance. Let me explain a little bit more. These are the bottom bell, which are hanging on the lower back and slamming against the bottom or the upper leg of the dancer. The flags, they represent each family, they move around the field in specific ways, and because they jump up and down, they also produce the clinking sound of bells. The songs are a very unique literary achievement in the world of indiginious people of Taiwan, there are 16 recognized tribe now, this is considered really a high point of local literary achievement, traditional art. It takes more than 5 hours to perform and the pattern of this performance Is really intricate and complicated. Numerical process going on with functional and structural line. Text line, vowelization, a refrain, according to certain rules, but the rules are also unique for every song and a little bit different. It’s really hard to learn it. There is not so many people who can do it, but there is more and more interest from young people to learn it.

The line dance is something a lot of people participate in, and we can now look at some video. So you can have an idea. What you will see here is the lead singer, and watch their step also. In the back there are the flags, in the right also. Lead singer, group joining. So, notice how they move in sync, they all neatly step together. In the back, in the distance, the line is very very long, unbroken, they also step in sync, but not as nicely as the front group. The singing is more or less in sync with the dance, but this is very often not the case. The bottom bells, you could hear, you hear them all the time. It’s a kind of beat, a base rhythm in the ritual. You can see them here. We just witnessed the opening, singing at the first night.

This is after three nights, early morning. There is, what is leftover of the singers. What is typical here, is that all the parts have difficult, unique tempi. For example, in the recording, the bottom bell had the tempo of 79, the song: 60, the step:60, the flag, we have a much faster pulse of 158. There are other moments I counted this, I checked this, I’m still doing that. It’s quite clear, very often, these tempi they don’t line up very well.

So, in the dance, we get some complication due to group dynamics. You see here, some people in plain clothes, not dressed in red and white. It’s people from outside, non-Saisiyat people. There can be all sort of things going on. Instead of moving right steadily, the group will start to move left. Instead of going forward, maybe part of the group is going forward. There are people entering, leaving. There is rice-wine-drinking, we are being fed by the Saisiyat people to drink to keep ourselves warm all night. Sometimes very small children dance. There is all kinds of things that could go on wrong particularly in the line dance, where up to hundreds of people can participate.

So, I’m talking about pulse and not about rhythm, because this is defined by long and short pattern. It’s really the tempo, this very basic thing of the pulse that Is going on across different media, like the song and the dance.

Pulse allows me to think more in terms of waveforms, where you can get transverse displacement. As well as longitudinal, the line sometimes getting very dense, and sometimes stretch out. You’re absolutely suppose to hold hands, and not to break the line. This is the sacred duty of Saisiyat.

When we would talk about in sync and out of sync, it kind of suggest we should be syncing up. But a group, inside a group there should be syncing. The bottom bells, they sync together, most of the time. The singers they step in sync, but these patterns don’t line up with each other often.

Now, let’s have a look at how it can go a little wrong. But still, this is non-disruptive, there is no physical tension in the body. It’s a regular step, of equal distance, and it is Saisiyat people. You see, they go left and right, they step. At some point, you notice and wave coming into this line. And here you see if happen, part of the line moves forward, part of the line move backward. In the distance, you see the core group of singers. This doesn’t happen to them. They always maintain their steady pace.

Now you see how it can go wrong. There is Saisiyat and non-Saisiyat people. In front you see stagnation, there is not movement, but you can have a look there. The Saisiyat move to them, the group got so much squeezed together, they are bulging out. This is kind of longitudinal wave. On the left, you see leading singers, dancers. You can see the shadows showing their step. The center is supposed to move clockwise, but they move anti-clockwise.

See the group bulging, Saisiyat move to them, they don’t know what to do, this is a group of people, probably, for the first time, they are interested to join, they are curious about this Saisiyat ritual, very mysterious, maybe it’s for leisure, maybe it’s for fun. They probably do once, maybe they do several time. But, they don’t really know where to go, and it’s too many people anyway, so the group dynamics makes thing go wrong. At the same time, the core group, the lead singers keep the steady pulse.

Now, there is a neat spiral I want to show you. It can go nicely too. These are mostly Saisiyat. You see there is counter movement of the group outside, and the group inside. The singing also, it continues in its own tempo, unstirred tempo. So there is these different pulses going on steadily.

There is great beauty, I think, in this spiral. It’s an incredible challenge if you think about it, and if you do it. So, the the pasta’ai is a sonic ritual with unique spatio-temporal features. And I will sum up some ideas here. It would be much easier to do things in sync. This is the natural tendency to synchronize, and to save energy. But there is no clear attempt to synchronize the parts, there are multiple pulses going on, actually, most of the time. So, any dancer and any singer, whether you are new or experienced, you are challenge to resist locking-in with other pulses.

The coregroup of singers-dancers often perform the same tempo for singing and dancing,but the steps of singers further down the line tend to go out of phase with the coregroup. All of them are close to the different pulses from the bottombell-dancers and flagbearers.

Across many of the spatio-temporal patterns (of song and dance) phase differences, phase shifting, and a-synchronous patterns are the rule, rather than the exception. These potentiallly disruptive forces result from group dynamics, are beyond the individual’s control, and are experienced by all active participants.

The dance form, deceivingly simple as it is, invites participation by outsiders and enables the commingling of Saisiyat ritual specialists, other Saisiyat as well as Han/Hakka Chinese, Atayal and foreign outsiders. Others.

Who participates in what? We’ve talked about the different musical parts, dance parts. These are all done by Saisiyat people. And, on the right side, you see curious outsider, people like me, and there could be up to a dozen of outsider who buys the suit. You may not see if they are Saisiyat or not. There are a lot tourist who just join. I think what is most striking, is that the core group to the left, they do everything to perfection, 100%. Sometimes the bottom bell go out of sync. The flag they have their own pattern. I think other Saisiyat and other outsider, they are able to do the line dance 75% to 90%. But for tourist, who often don’t have a clue what to do, when the group is too big, the correctness is perhaps 20-25%.

So, how to call it? I want to emphasize, this is not polyrhythmic. Polyrhythm, it suggest, in the end, that there is a common cycle. There are multiple time cycle, and they get together at a certain point. That is not happening here. So all the different poly we have, we now don’t talk about polyphony, we talk about multi-part music. I want to call, what I found out here: multitempic, and multitempic structure. And, I’m curious to hear, if any of you know any multitempic structure. I think it is pretty rare. I would mainly think of avant-gard, or free jazz music kind of thing. But there must be few examples, perhaps in the Amazonian rain forest, or something like that.

I’m going to slowly go to my conclusion. The Pasta’ai might well have received new dramatic input over the last decades: slower, more dragging tempi, with long-held notes that keep a clear pulse floating for such a long time, that it seems to beg to be disrupted by competing tempi.

There is a wonderful 3CD box, re-issued recently, by our moderator Wang Ying-Fen. A very nice box of traditional music of all the tribe known to the Japanese. There we read the bottom bell were worn by the singers, and they would synchronize bottom bell, step, and singing on the recording. So, that is different from what we hear nowadays.

Concluding remarks, then. Echoing anthropologist Chia-Yu Hu, I conclude that the Saisiyat adapt their ritual behavior to address changes in society. They adapt and adopt, but do not succumb to the Other. They are inviting and welcoming, but resist appropriation. The Pasta'ai is the ultimate platform of the Saisiyat meeting the Other and the Other meeting the Saisiyat, celebrating both the benefits and disadvantages for both parties.

With my own eurocentric gaze I believed in an idealised version of the Pasta’ai where all the parts/pulses link up neatly in ideal, carefully ‘orchestrated’ and ‘choreographed’ parts.

I now would argue that the multitempic structure danced, played and sung by the Saisiyat of Wufeng has phase shifts, disruptions and frictions, has successful as well as unsuccessful spirals embedded in its very design.

Sometimes danced by as many as hundreds of people, the Pasta’ai reflects and creates society from the Saisiyat’s perspective as it really is, with its colonial echoes, in its postcolonial reality, and its de-colonising ideals.

向前走,或是向後退?

台灣巴斯達隘祭典中賽夏族與漢族的族群共處

Mark van Tongeren, 獨立學者,台灣

幸運的,我所要討論音樂: 巴斯達隘(矮靈祭)祭儀每兩年舉辦一次。今天儀式正要開始,我等下就要出門參加三個整夜的儀式。我第一次參加矮靈祭是在2004,16年前。過了16年後,我終於覺得可以開始試圖用文字梳理這個精密、令人著迷的儀式。我也覺得很受到kuku ta’ai (矮靈),這個儀式所祭拜的矮靈,的祝福。當我在準備這個演講的同時,矮靈祭的準備也正如火如荼的進行中。整個儀式期間其實是一個月的時間,而只有這個月的儀式準備期可以唱祭歌。我覺得很幸運當賽夏族人在準備祭典時,我也可以準備我關於矮靈祭的發表,同時,我也參與了幾次部落的祭前練唱。

我要討論的是賽夏族。賽夏族住在台灣的西北部,投影片上看到那個小扇型。他們是少數中的少數。當然所有台灣的原住民族加起來只佔台灣人口的少數。賽夏族目前人口大約6600人,真的不多。他們住在不同的聚落,並且日本殖民時期他們分成兩個領地。

矮靈是曾經居住在此地的矮黑人,但他們被賽夏族殲滅,傳說中是如此。我要探討的是非賽夏族人參與矮靈祭對於祭儀傳承及傳統知識的威脅,以及儀式歌舞脈動的時空組織結構。

回到第一個問題,目前有很多人參與矮靈祭,我讀過人數兩萬人的統計紀錄。問題在於,他們會干擾儀式的進行嗎?我沒辦法完全靠田野訪問來回答這個問題,因為我的中文今年才變得可以跟當地人溝通。賽夏族人大都不說賽夏語,中文還是主要語言。而我也依靠胡家瑜的論文,給我了許多探見賽夏族身分認同的觀點。

賽夏族幾世紀以來,都跟鄰近的族群通婚。他們不抗拒跨族群的通婚。而通婚影響了他們的習俗,影響層面包括語言、名字,族人都慣用中文名;別族或殖民者引進的科技。通婚跟領養在過去很盛行,至今仍常發生。

賽夏族人有很大的開放性,他們的文化適應跟融合也很強,而很多人會覺得很好奇: 他們到底是怎麼保有他們的身份認同呢? 賽夏族跟很多族群有曖昧的關係,他們會向強勢族群(人口比他們多更多)的人學習;科技比較先進的,可能是魔法能力,像是被他們殲滅的矮靈學習。這些族群都為他們帶來一些好處,他們也需要、想要這些好處。但還是有些缺點。

矮靈的故事很重要。故事是這樣的: 矮靈是住在賽夏族附近的一個族群。兩族常有互動。賽夏族人向矮靈學習耕種,也很欽羨他們的魔法能力。但是矮靈也會騷擾賽夏女性。有一次,在一次的慶典之後,矮靈回到他們的居住地。一個賽夏男人發現他的老婆被矮靈戲弄了,所以他決定要報復。矮靈習慣休息的地點是一棵樹稍懸掛於河谷懸崖。賽夏男人太生氣了,他把樹鋸斷,矮靈都跟著樹墜入河谷而死。最後只有兩位矮靈倖存,他們回到賽夏的部落,並對他們說: 「你們必須學會我們的歌跟舞蹈,一代代的傳下去。這是你的責任,如果你不這樣做,厄運會降臨整個賽夏族群。」這個想法目前還是很貼近賽夏族人的認知跟情感,縱使矮靈幾百年前就滅絕了,賽夏族人還是深切的記憶這個故事。

學習矮靈的歌舞非常困難。雖然之前賽夏族與矮靈曾多次的共舞,學習整套歌舞真的很難。最後,兩位矮靈終於找到一個家族的人比較擅長歌舞,而這個家族至今仍然領到矮靈祭的歌舞祭儀。

除了跟矮靈關係中,賽夏族人跟它者的互動中也有同一個模式。可能族人羨慕科技或其他族擁有的東西,而做了一些導致失去、死亡甚至於滅絕的活動。最終帶來悔恨,和自食惡果的折磨。

人類學家胡家瑜的論旨,重述如下:

這個矛盾的情感複合體透過口傳神話被凸顯,並型朔出賽夏族精神的特色。這個和他者的關係,適用於神話中的靈像是達隘(矮靈)—神靈界的存在。但其關係也適用於現實世界中的鄰居,像是泰雅族、漢族、以及1895-1945年間的日本殖民者。

我想引用她寫的另一段文字:

「透過週期性的儀式行為,現代與祖先的時代的連結被建立;符合當代情節的新元素也被引進入儀式之中。從這個面向看來,儀式中所呈現的賽夏族集體的過去能夠橫跨地理、語言和文化隔閡達成高程度的內部整合。」

這解釋了身處於強勢族群跟殖民者的環境影下的賽夏族如何持續保有高度的身份意識。

我從以上的資訊形成了以下論旨:

巴斯達隘從來不只關乎賽夏族。它也總是涵蓋了它者。賽夏族充滿自我意識的(再)交涉—他們自身與握有權力它者的關係。他們很大程度上已經被同化,但仍透過舉辦儀式來維持高度的身份意識。

那,衍伸出的一個問題是:

「族群間的融合/互相共處是怎麼發生的?

回應以上的問題,我要檢視巴斯達隘音樂與舞蹈脈動的重疊與交織的時空組織結構。

我的研究範圍是我最後一次參與的矮靈祭,還有我今晚可能即將參加的矮靈祭。研究的聚焦在三天正祭,因為祭典期間大約橫跨一個月。

我的論點是: 新竹五峰的矮靈祭有個嚴謹的時空組織結構,由四個持續的,不同拍節的聲部構成。所以不是一個複音音樂的結構,而是由不同拍速所構成。我稱之為: 「多拍節結構」。第二個論點是: 完成其歌與舞需要高度技巧,雖然表面上看來,一些動作(舞蹈)跟聲音(音樂)聲部看似簡單。論點三: 看似簡單的動作(舞蹈)跟聲音(音樂)聲部,讓儀式能夠接納且對完全沒有經驗的外來者來參與。

聲音與動作的結構元素的四個脈動分別是: 臀鈴、肩旗、祭歌、舞蹈的隊伍。我再深入解釋一下。臀鈴,懸掛在下背,它會晃向舞者的臀部或大腿。肩旗,代表每個家族的榮耀,它們在祭場上以一種特殊的方式移動,而因為它們持續上下跳動,也會發出鈴鐺的聲音。祭歌是法定16個台灣原住民族中,非常獨特的文學成就,傳統藝術的巔峰。祭歌的非常複雜跟精密,篇幅長,唱一次要五小時。唱的時候需要數數,有些樂句反覆的設計,加上實詞跟虛詞的變化。歌詞,虛詞跟反覆次數都有各自的規則,但每首歌的的規則都不一樣。祭歌很難學。沒有很多人會唱,但是越來越多年輕人開始學習了。

很多人會加入主要的舞圈。我們現在可以看一下影片,比較能理解。這邊是領唱的人,祭歌組。可以看看他們的腳步。後面跟右邊有肩旗。這是祭歌組,這是被帶領的人。可以看到,他們步伐一致。舞圈後面,到很遠的地方,這個舞圈是很長,沒有斷口的。他們步伐都一致,雖然動作沒有前面的人俐落。歌聲跟腳步差不多是同步的,但這其實不常見。你可以一直聽到臀鈴的聲音。它好像是一個拍,一個儀式中持續不斷的基本節奏。這是正祭第一天入場的錄影。

這是過了三個晚上後的凌晨。場上剩下了一點人。這個儀式音樂的常態是: 每個聲音分部都有獨特的拍節。例如說,這個錄影中,臀鈴拍速是79、祭歌跟不乏拍速是79,肩旗拍速跟脈動特別快,它是158。我常在祭場上數拍數,我在不同的時間點檢視聲音分部的關係。我蒐集的資訊反應出: 這些拍速通常都各自有各自的特性。

在主要舞圈中,我們會因為團體動能而有些複雜的現象產生。影片上,穿一般衣服,沒有穿上紅白色祭服的人是非賽夏族的觀光客。舞圈中,有很多是同時發生。應該要往右的時候,有人往左。所以當隊伍要往前時,有些人是往後的。有人進入或離開舞圈。有人在喝小米酒,賽夏媳婦會下來舞圈敬酒,喝酒讓唱歌的人身體保持溫暖。有時候,很小的小孩也會在舞圈中跳舞。幾百人同時參與主要舞圈的時候,情況會變得很複雜,很多雜訊會干擾舞圈運作。

我討論的是脈動而不是節奏。節奏是長短的組合。而我討論的重點其實是拍速,也就是不同聲音分部中像是祭歌跟舞蹈中,延續不斷的基底脈動。

脈動這個詞彙,讓我能用波形的概念來思考。有時候有錯位的橫波,有時候產生綜波 (五圈隊伍有時候會密集,有時候拉的很長) 。不管如何,手都要握緊,不能斷。這是賽夏族神聖的責任。

當我當討論合拍或不合拍時,我們預設合拍才是和諧的。當然,一個聲部應該要有統一的拍速。臀鈴,大部份的時間中,整組人都是同一個拍速。祭歌組的歌與舞是合拍的,但祭歌組跟臀鈴組兩組各自的拍速不同。

我們現在來看一個不完美的例子。不過,這個雖然不完全是對的,但還是很平和的,舞圈裏面的人的身體還是處於放鬆狀態。賽夏族人們的步伐是規律,等距的。他們先往左,再往右,邁出一步。然後,某個時間點,你看到舞圈中有波浪形成。為什麼呢? 因為舞圈中有一段的人是往前邁,同時,有一段的人往後踩。祭歌組在畫面中很遠的角落,但你可以看到,他們沒有發生這種情形。他們的步伐都是同步的。

這是一個混亂的例子,有賽夏跟非賽夏族的參與。前面這邊擠成一團,動彈不得。然後這裡,賽夏族人往這邊移動,然後被夾在中間的這群人被擠出來,凸出舞圈。畫面的左邊是祭歌組。從他們的影子,可以看到腳步。螺旋的中間應該要順時針移動,但目前是逆時移動。

凸出舞圈的那群人,他們不知道要做什麼。他們可能第一次參與舞圈,他們只是對於神秘的賽夏族儀式很好奇,或是他們只是想找些新的休閒娛樂。他們可能參加過一兩次,但他們不知道要往哪邊走,然後人真的太多了,所以團體動能就會很複雜、出錯。不過,在此同時,祭歌組跟歌跟舞都很穩定不受影響。

現在要給大家看一個美麗的螺旋。螺旋也可以呈現很和諧的狀態。這螺旋裡大多是族人。你可以看到螺旋裡面跟螺旋外面相抗衡的動作。祭歌組跟歌跟舞都很穩定不受影響。所以幾個不同的脈動都持續穩定的存在著。

我覺得螺旋很美,它看起來很簡單,但運作起來一點都不容易。矮靈祭是獨特的聲波儀式具備獨特的時空組織結構。我在此總結一些概念。身體與聲音在同一個節奏之中(同步)要比在不同步的節奏容易。身體的自然慣性是同步規律以節省能量。在祭場上,反常的,沒有同步的現象,相反的,場上有很多節奏脈動共存。不管是老鳥還是菜鳥都要克制和其他脈動同步的趨勢。

對於祭歌組的人來說,他們必須同時執行祭歌及舞步的脈動。但非祭歌組,接在舞圈比較後面的人,舞步常常會不同步,臀鈴跟肩旗的聲音可能會把他們的步伐拉走。橫跨許多時空組織結構(很多歌舞曲目)律動差異性、律動轉換,與不同步的模式是主要的特徵,而非例外。這些由團體動能所產生的衝突性能量,在個人的掌控之外,但被所有人經歷。

看似簡單的舞圈,歡迎著外來者的加入使得賽夏祭典的傳承者、其它賽夏族人、漢人、客家人、泰雅族人、外國人可以在同一個場域中融合共處。

哪些人會加入哪個隊伍呢? 我剛剛說的臀鈴、肩旗只有族人可以參與。畫面右邊,你可以看到很多對儀式好奇的人,十多個像我一樣像我一樣買了族服的非族人。還以很多直接參與的觀光客。我覺得最令人敬佩的是,畫面右邊的祭歌組他們幾乎100%完美的執行歌舞。而,臀鈴有時候會有不同步的狀況。肩旗有各自的節奏不列入評論。我認為非祭歌組的族人跟穿族服的外人,可以執行75-90%正確。但觀光客,通常沒有接觸賽夏文化,然後舞圈人太多又太混亂的時候,動作正確率只剩20-25%。

如何稱呼這獨特的時空組織結構? 我要強調,絕對不是複節奏。複節奏的定義是:有多個節奏長度同時存在,在某個時間點、某個週期他們會同時會到原點。這不適用此例。我們也不是在討論複音音樂,而是有多個分部的音樂。我想將其稱之為: 多重節拍,多重節拍結構。我也很好奇在座的各位熟悉其他多重節拍音樂的例子嗎? 我覺得它蠻罕見的。我會想到前衛音樂,或是自由爵士。但其實應該會有更多多重節拍的例子,可能在偏遠的亞馬遜雨林,或其他地方。

巴斯達隘在過去的幾十年,可能累積了戲劇性的新元素挹注: 更緩慢,更延長的節奏,加上一個延展的長音—長時間持續的提供一個漂浮在上的清楚脈動,其效果似乎是挑釁其他競爭節奏將其打斷。

我們的會議主持人王櫻芬,最近有個重新出版的一個很棒的3 CD (戰時台灣的聲音1943: 黑澤隆朝 《高砂族的音樂》復刻—暨漢人音樂)。 裡面有日治時期戰前所蒐集的傳統音樂。當時的錄音中,唱祭歌的人同時也戴臀鈴,臀鈴、舞步、祭歌都是同拍的。這跟我們現在聽到的聲音不一樣。

結語。延續人類學家胡家瑜的論點,我認為賽夏族透過調整儀式行為來回應社會的變遷。他們適應和接受,但他們不會對他者低頭。他們邀請和歡迎它者,但抗拒外來文化的直接挪用。

矮靈祭是賽夏族與他者相遇,和他者與賽夏族相遇的最高平台。為雙方各自帶來好與壞。

由我自己的歐洲觀點出發,我相信矮靈祭有個理想的設計,每一個部分/ 脈動都巧妙的連結起來,都非常理想及巧思的被「指揮」和「編舞」。

我認為矮靈祭的多重節拍結構: 五峰賽夏族的舞蹈及歌唱有 律動轉換、間斷與摩擦,它初始的設計之中概括了成功與失敗的螺旋。

矮靈祭有時能有上百人同時共舞,它反映和創造了賽夏族社會最真實的面貌,有著其殖民過往餘韻、後殖民的現實,以及去殖民的理想。